The church of Seiffen

Was there a church in Seiffen before the present one?

As we have seen, those Cistercian monks, the first miners of Seiffen, were Christians. Praying and singing belonged to the way they lived. They probably had a small transportable altar (see picture below). It is possible they built a small church of wood. However, we do not know where it stood and what it looked like. For sure we know that our graveyard existed as early as 500 years ago, in the 16th century.

The first pieces that give evidence of a church date from about 1560/70: the oldest cup that was used to celebrate the Lord’s Supper (1560) and a painted window of the first Seiffen church (around 1570). The latter can now be seen at the Freiberg Museum of Mining.

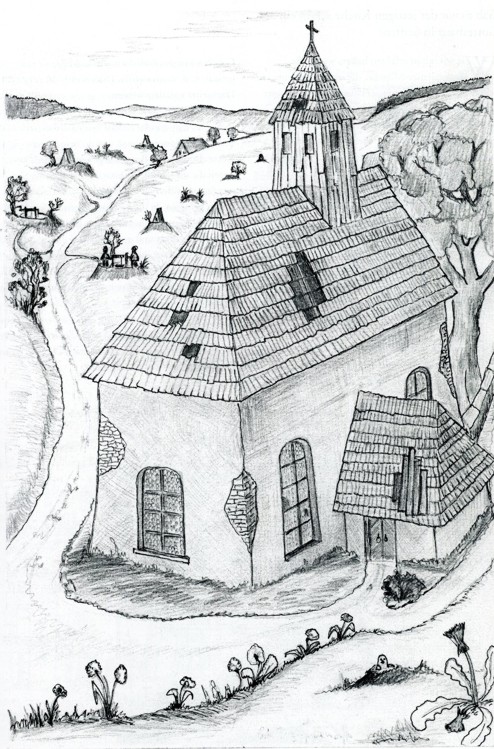

What did the church look like? It showed a rectangular shape, the roof bearing a monitor (small tower) where the bells hang. Several times, the church was subject to construction work, e.g. repairs done to the monitor in 1676, 1686, 1730.

|  |

There is no doubt the old church was mainly used for funerals and for the quarterly services held for the miners. Such services were mostly held in May, July, October, and January. The same as today, pastors read from the Bible and gave their sermons. The community prayed, sang songs, celebrated the Lord’s Supper. In addition, the pit fore-men reported about work, warned miners to observe the health and safety regulations, and to follow the moral standards of the time. Generally, however, Seiffeners went to services in the Neuhausen church. The pastor there also tended Seiffeners. | |

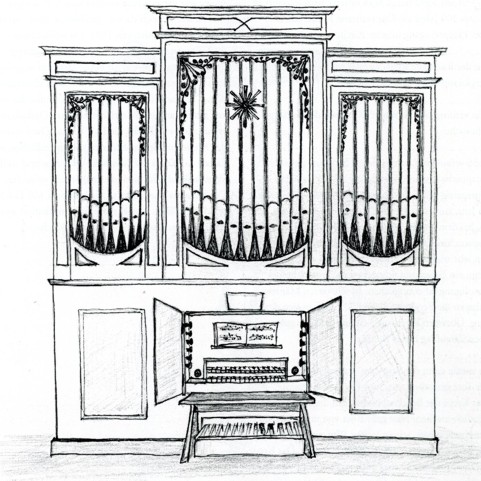

In addition, one more register is sounded today known as cymbal star. It refers to the golden star which the central pipe on the front of the organ shows. It can be operated by means of a switch. The star then rotates and three small bells are sounded in the organ interior. This is how our ancestors expressed both the joy they felt at Christmas and their certainty of eternal life.

| 1st manual (main manual) | 2nd manual (upper harmony) | Pedal |

| Principal 8' | Hollow flute 8' | Profound bass 16' |

| Bordun 16' | Tube flute 4' | Trombone bass 16' |

| Viola da Gamba 8' | Third cymbal 3f. | Principal bass 8' |

| Lovely-thought 8' | Principal 2' | |

| Pointed flute 4' | ||

| Quint 2 2/3' | ||

| Octave 4' | ||

| Octave 2' | ||

| Mix 2', 4f. | ||

| ||

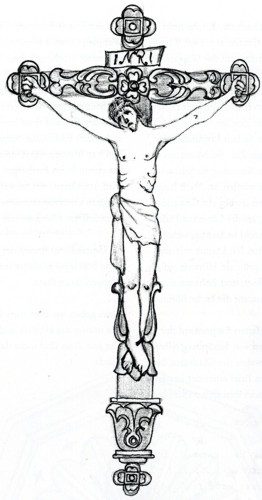

The cross of the Miners’ Guild of 1688

The cross of tin hanging over the main entrance is 300 years old, but it has hung there since as late as 1992.

An inscription on its reverse side reads: To the Miners’ Guild of Seiffen.

What is the story behind? What was the cross used for?

Aiming to help each other, a number of Seiffen miners founded a guild in 1686. Every Shrove Tuesday they gathered for a meal, at which opportunity they also talked about their sorrows, sang songs, or played games. A miner dying, they saw to a funeral in dignity. Wearing black coats, miners attended, some of them bearing the coffin. Laid on the coffin was a large cloth with the particualr cross of tin on top of it.

The coffin was taken from the deceased one’s home to the graveyard. The Miners’ Guild’s cross expressed that one of the guild was going his last way – or as miners said: was doing his last shift. The cross also said that a man had passed away who believed in Jesus Christ the crossed and the risen one. He who relies on him in his lifetime will also have him by his side when he must leave from here. He can hope Jesus Christ includes him when saying: I live so you shall live, too (John 14, 19).

From an antique list which is deposited in the Freiberg Museum of Mining we learn how much the guild spent on the cross: 3 talers and 4 groschens to buy it, 1 taler and 12 groschens to have it painted and gold-plated, 7 groschens to have it transported to Freiberg.

For long, the cross seemed to have disappeared. Nobody knew it was still there. This changed in 1991 when a Seiffener watched teenagers excitedly jumping around a car. When they left for a short moment, he checked the car where he found that particular cross. He realized he had to stop the driver travelling on so he inflated all tyres. Then, he took the cross with him. The teenagers claimed they had found the cross in a landfill and were going to sell it to a Dutch antique dealer. That did not work! They were given 100 deutschmarks to comfort them. Since 1992, the cross has hung in our church.

| |

Lange war dieses Kreuz verschwunden. Niemand wußte, daß es noch da war, geschweige denn, wo es lag. Das änderte sich erst 1991. Da beobachtete ein Seiffener ein Auto, um das Jugendliche aufgeregt herumsprangen. Als sie für einen Moment weggingen, schaute er ins Auto hinein und sah darin eben dieses Kreuz liegen. Sofort war ihm klar: Er mußte das Auto erst einmal an der Weiterfahrt hindern. Deshalb ließ er aus allen vier Reifen die Luft heraus. Dann nahm er das Kreuz mit. Später erklärten die Jugendlichen, sie hätten das Kreuz auf dem Müll gefunden und wollten es an holländische Antiquitätenhändler verkaufen. Doch daraus wurde nichts! Sie bekamen 100 D-Mark als kleinen Trost. Das Kreuz konnte restauriert werden und hängt nun seit 1992 in unserer Kirche. |

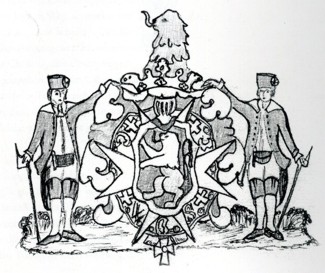

The Mining Office’s coat of arms

The two galleries to the right and the left of the altar show coats of arms. Looking the direction of the altar, we see the arms of the Schönbergs who ruled the region from 1389 to the middle of the 19th century. It depicts a red and green lion in the middle of parts of a knight’s harnish. The lion generally stands for a good and rightful ruler. As for the red and green colours, people say that many years ago, one of the Schönberg family was part of a crusade to Isreal where he was attacked by a lion. After a long fight he was able to drive the beast into a lake where it drowned. Pulling the dead lion out of the water, he noticed it was covered in greenish water plants. A nice story. Yet I can imagine the red and green colours refer to the neighbourhood of Saxony (green) and Bohemia (red).

Back to the galleries. The right-hand one was not where the Schönbergs sat, no, seated there were the superiors of the glass-works. We know a letter of 1887 where one of the last glassworks superiors confirms this seat meant very much to him. On the left-hand side there is another coat of arms which is held by two miners dressed in black. These are the arms of the Seiffen Mining Office. Superiors there looked after mining until 1849. They negotiated a certain range of matters such as the right to start a mine. Their decisions were entered into a particular diary. Entries go back as far as 1685, the diary itself being exhibited at the Freiberg Mining Archives. There we can learn who did what in the Seiffen mines. The senior miners of those days thoroughly took down all the details. At services, both the senior miner and his assistant sat in that glazed gallery with the particular arms.

But let us be honest: Due to the fact that tin was mined in Seiffen (not the more valuable silver), the Seiffen Mining Office was the smallest and poorest in Saxony.

| |

| Im Gottesdienst hatten der Bergmeister und wohl auch seine Schreiber in dieser verglasten Empore mit dem Wappen ihren Platz. Eines geben wir aber ehrlich zu: Das Seiffener Bergamt war immer das kleinste und ärmste in Sachsen, weil hier nur Zinn und nicht das teure Silber gefunden wurde. |

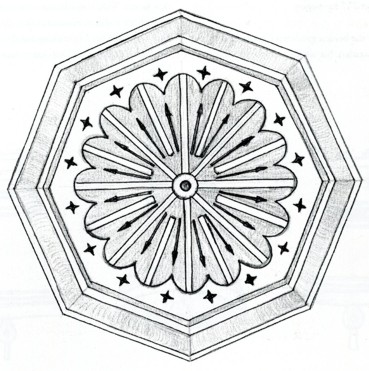

The octagon

If you lift your looks up to the ceiling, you can see what is printed at the bottom of this page: a rosette. Advent coming, the hole at its centre serves to channel a rope that holds two traditional decorative elements: a star and a wreath. The rosette also gives you a good idea of the floor plan of our church, which is octagonal. Yet it happens our church is taken for being round. In the old days, eight was looked upon as a symbol of God’s eternity. A week counting seven days, it stood for man’s time. Eight being beyond seven, it represented God’s measure. The eigth day is the day of Jesus arising. This is why in the past, churches were often built to octagonal floor plans (see the church of Ravenna, the baptismal church close to the famous Leaning Tower of Pisa (both in Italy), the Palatinate Chapel at the Aachen Cathedral. Or think of the Dresden Frauenkirche where the dome is borne by eight pillars. To some degree, the architec-ture of our church is inspired by it.

|

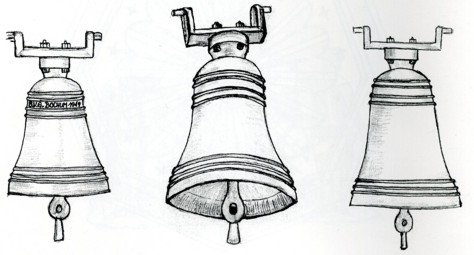

The bells

In most cases, you cannot see them, yet the bells are essential to any church. Our bells sound both at the beginning and at the end of services. We also ring them thrice on every working day, and they are heard at a long distance. The bells’ ringing is far from everyday noise. The bells ring to invite you to pray. At least, a Christian should know by heart the Lord’s Prayer. The larger and heavier a bell, the deeper it sounds. Generally, bells are of brass, a blend of copper (78%) and tin (22%). Today, we ring the fourth set of bells. In 1779 the very small bells of the preceding church were taken over. New bells weighing only 200 kgs in total were cast in 1790. They still were of a very modest size. Ringing them on Good Friday in 1849, the largest broke. Luckily, still in the same year our church was equipped with new chimes, which weighed no less than 747 kgs. It is sad to say the two larger bells were taken down in 1917, their metal being made into weapons (time of the First World War). Then, for as long as 1920, the church could ring only one bell.

In 1920, the entrepreneur Thomas Morgenstern gave the church three new bells which we ring until today. They were cast in the city of Bochum in 1919. Their sound scheme is h – d – e. Their weights are 340, 230, and 145 kgs (715 in total). Their bottom diameters measure 910, 798, and 680 mm. In those days, they cost 3, 575 marks. Unfortunately, they are not of brass but of cast steel. Bells of brass lasting hundreds of years, those of steel or cast steel start rusting after only about 80 to 100 years and may even break. Consequently, we need to think of new bells in the near future. It is worth mentioning that the only (small) bell that survived the First World War is still in operation: Since 1957 it has been installed at the Lauterbach (a village near Marienberg) fortified church, from the tower of which it can still be heard ringing.

| |

Während Bronzeglocken viele Jahrhunderte halten, fangen Stahl- und Eisengußglocken nach etwa 80 bis 100 Jahren von innen stark zu rosten an und können sogar zerspringen. Das heißt: Irgendwann in den nächsten Jahren brauchen wir neue Glocken. Eines ist noch zu berichten: Die alte kleine Glocke unserer Kirche, die 1849 mitgegossen und als einzige den Ersten Weltkrieg überdauerte, stand noch einige Jahrzehnte auf dem Kirchenboden. Seit 1957 läutet sie in Lauterbach bei Marienberg auf dem kleinen Turm der alten Wehrkirche. Dort kann man sie bis heute hören. |

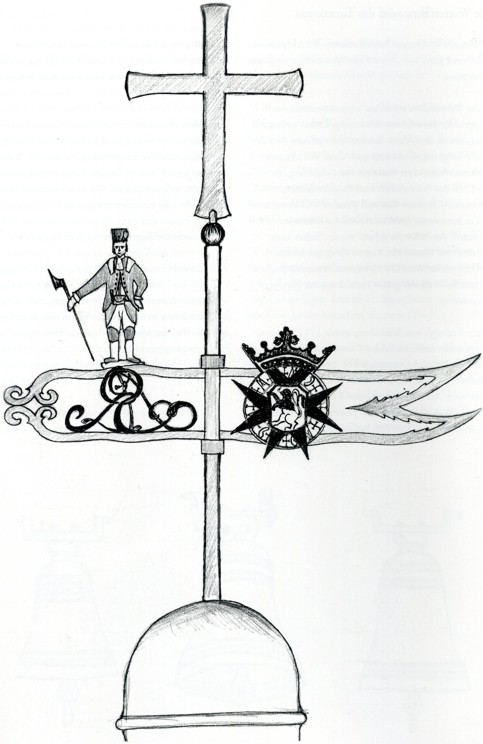

The weather cock and the cross on the tower of our church

Approaching the end of our tour, let us have another look up to the weather cock and the cross on the tower of our church.

Embedded in the weather cock is the coat of arms of the Schönberg family. We remember the man who contributed much to the erection of the church and who gave us this very weather cock: Adam Rudolph of Schönberg. He started off construction, he appointed Christian Gotthelf Reuther the builder. Very likely, he decided the church was going to be octagonal. For sure, he had another church in mind which he knew well and which all of us admire: the Dresden Frauenkirche.

Adam Rudolph of Schönberg was born in 1712. He was active at Purschenstein Castle as well as in Reichstädt and Dresden where he filled the post of Saxon Senior Postmaster. Unfortunately, he was not married so he had no children. He died at the age of 82 in 1795 and was buried at Reichstädt Castle. The miner in the weather cock reminds us Seiffen started as a place of mining so at its beginning, our church served the miners. This is why it is known as a miners’ church. On its highest top, we can see a gold-plated cross. At a height of 34 metres above ground level, it confirms that Jesus Christ is Master here, the man who died on the cross and rose at Easter. Christians strongly believe that he is alive today and forever. He has promised us, “I am with you until the edge of doom.”

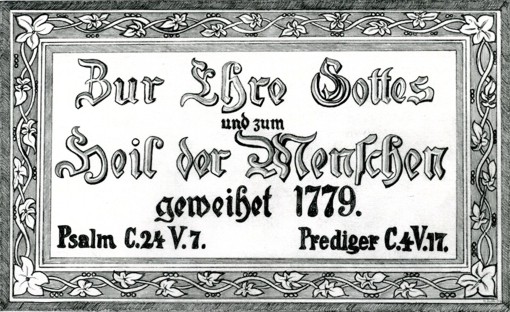

Our church exists since this is true. Above its entrance we read TO HONOUR GOD AND TO SAVE MAN. Together with many other people, the two of us, pastor and senior miner, feel sure this will guide us into the future.

| |

| |

| Our special thanks goes to the church of Seiffen, in particular Mr Pastor Michael Harzer and Mr Bergmeister Günther Zielke for providing us with text and graphical material. If you wish to get further information about the church in Seiffen we recommend you a visit of the homepage www.bergkirche-seiffen.de/. |